Born in Seoul, Yehwan Song lives in New York, but her work encompasses many different kinds of borders.

(Michela Zoppi) Your background in graphic design has been shaped by a digital world that is quickly changing and taking over communication methods, behaviours and physical reality at large.

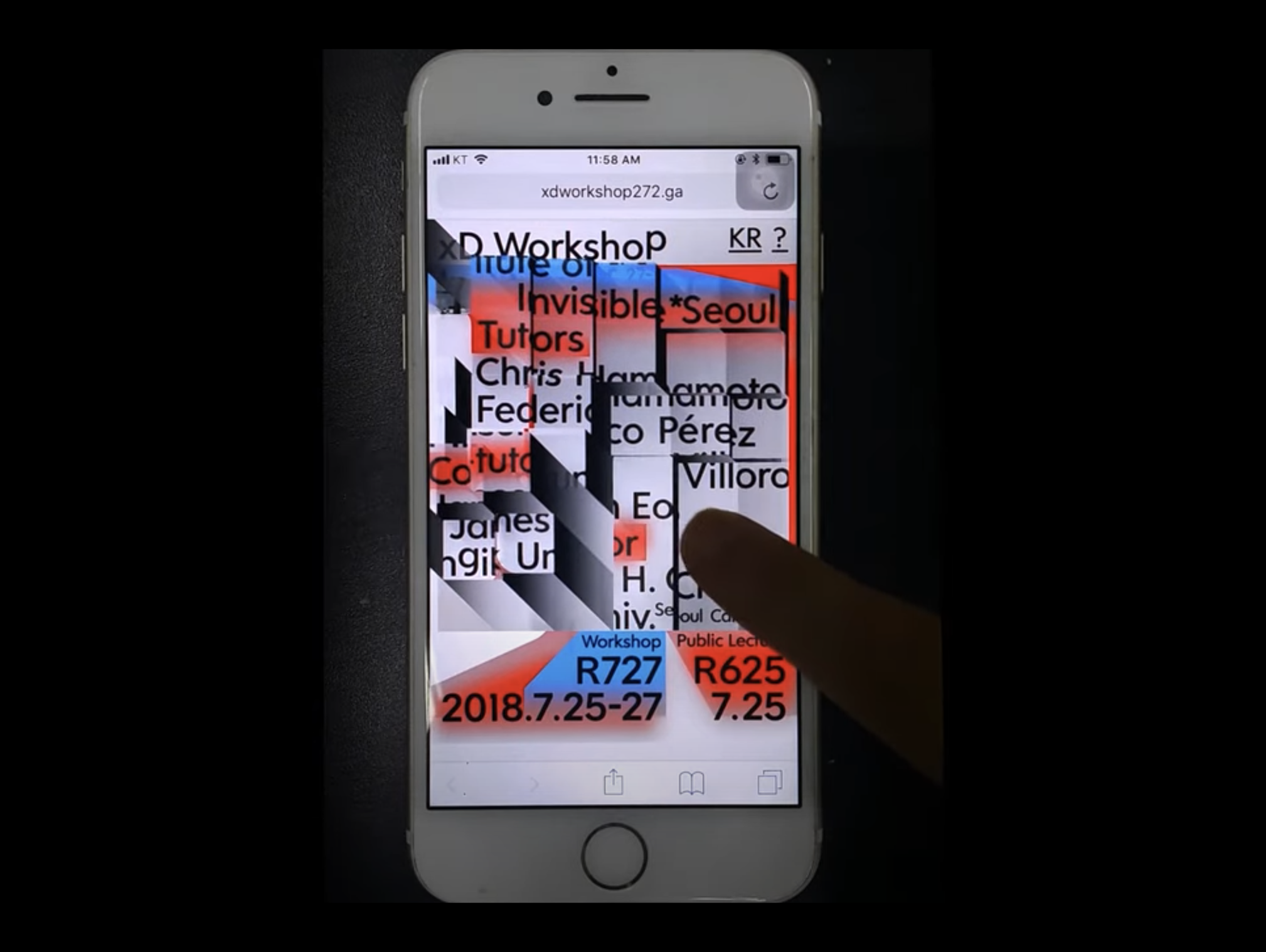

(Yehwan Song) People from my generation, especially young designers, started to engage with digital media on a deeper level. From sharing works on image-based social platforms to approaching website design, the opportunities given by these seemingly uncharted worlds fascinated me from very early on.

(MZ) The fast developments of the digital space, with its trends and aesthetics, must have ignited questions on the possibility of new design languages.

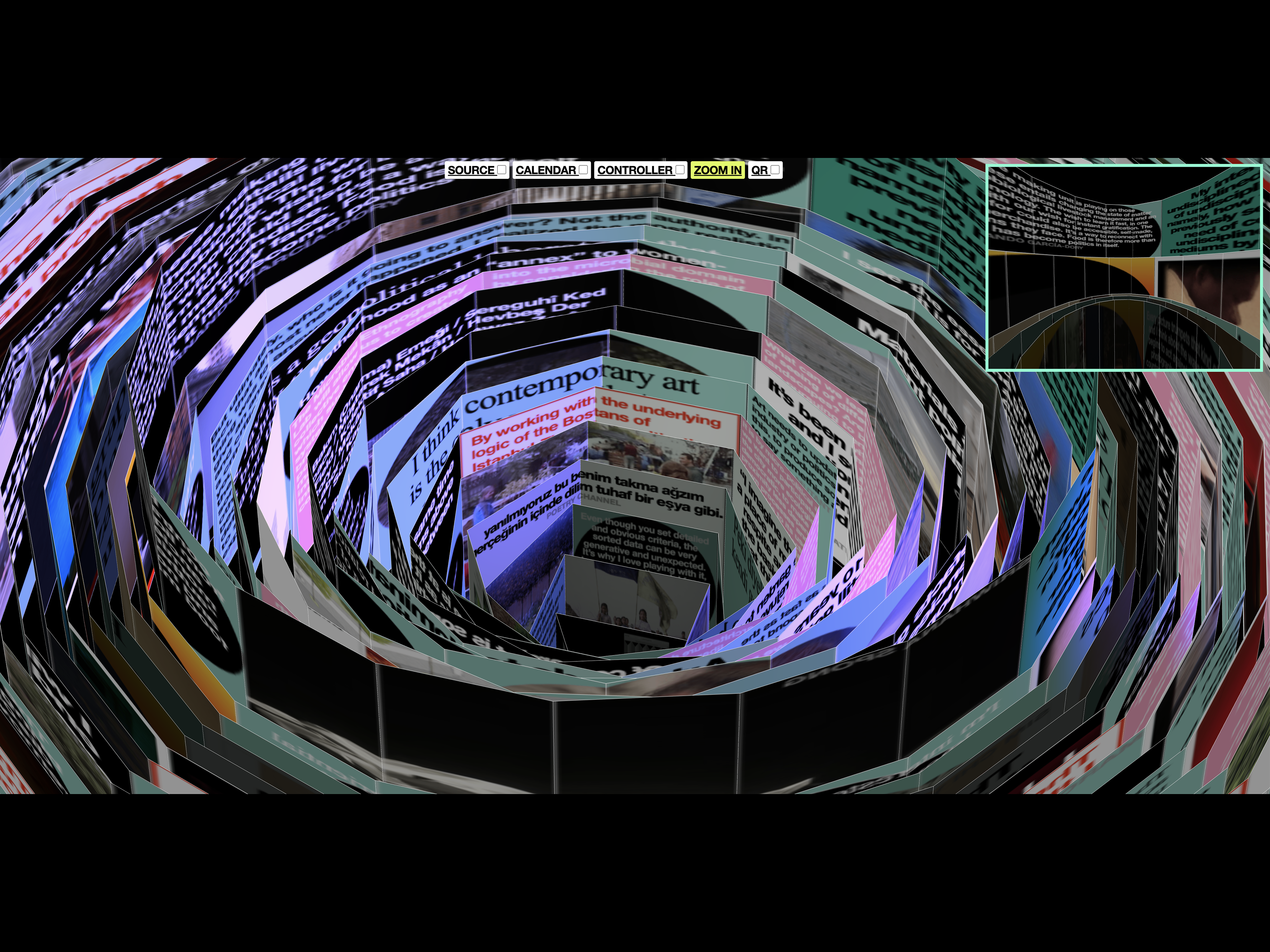

(YS) I started to realise the growing power that digital platforms were acquiring: the possibilities of changing, and manipulating the content, aesthetics, and tools. Communication assumed very different methodologies, transcending cultural locality and, more in general, time as we understand it.

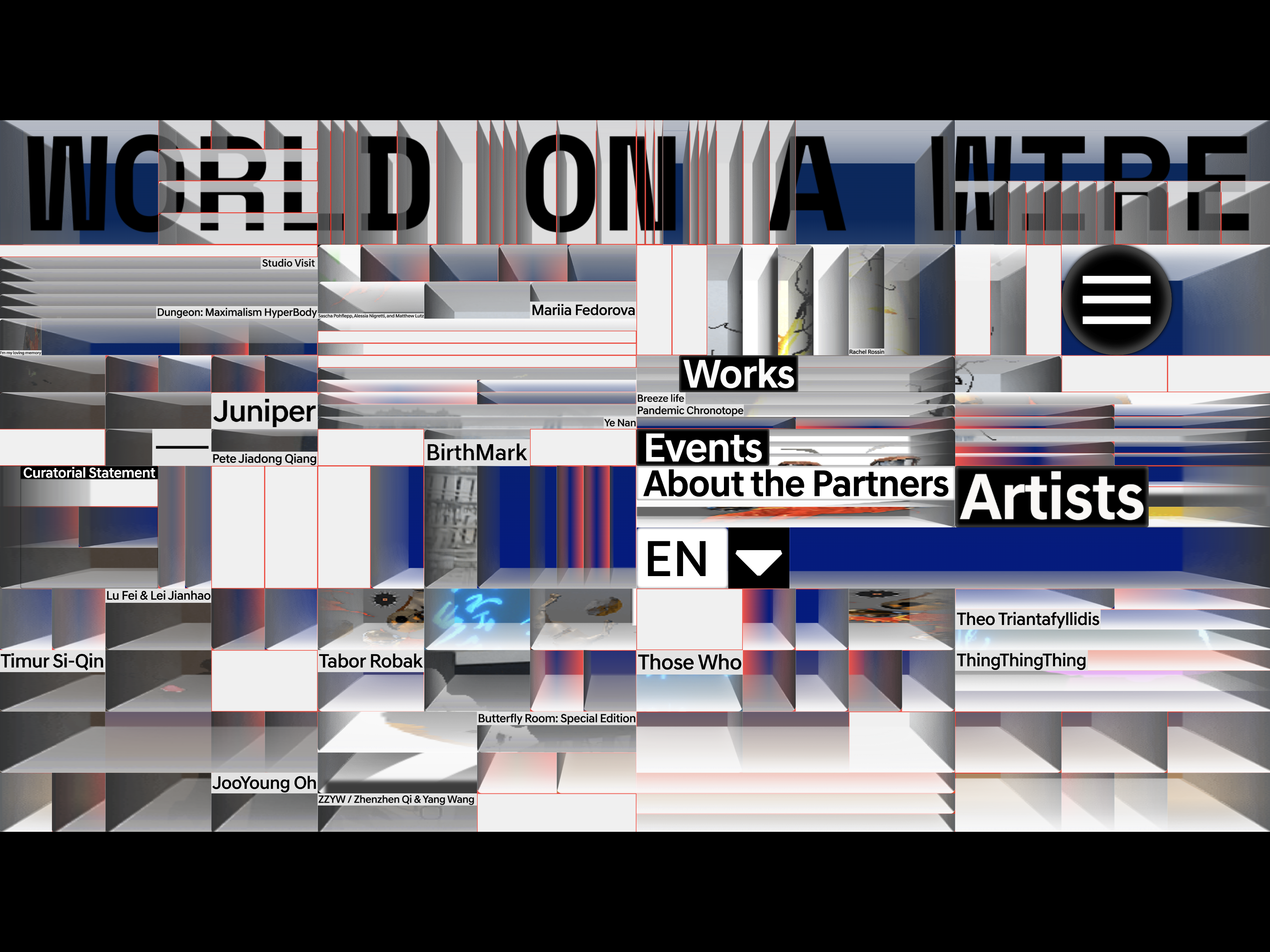

These evolving new languages and tools sparked my interest in how digital platforms showcase and share people’s thoughts, connect groups, and present content of different kinds. I began to look at what’s underneath; I was mining its underpinning systems and structures. Eventually, this acquired knowledge instigated work that would respond to what I was seeing.

(MZ) Our bodies are shaped to survive in a physical reality, but technology is pushing society to migrate to the digital world. A concern of our contemporaries is related to the progressive impact of de-materialisation on human interactions with their environment.

(YS) I believe technology is still unable to replicate our sensorial perception of physical reality; we feel, smell, touch, share energy, and breathe in the real world. However, we can only have a restricted digital sensorial experience.

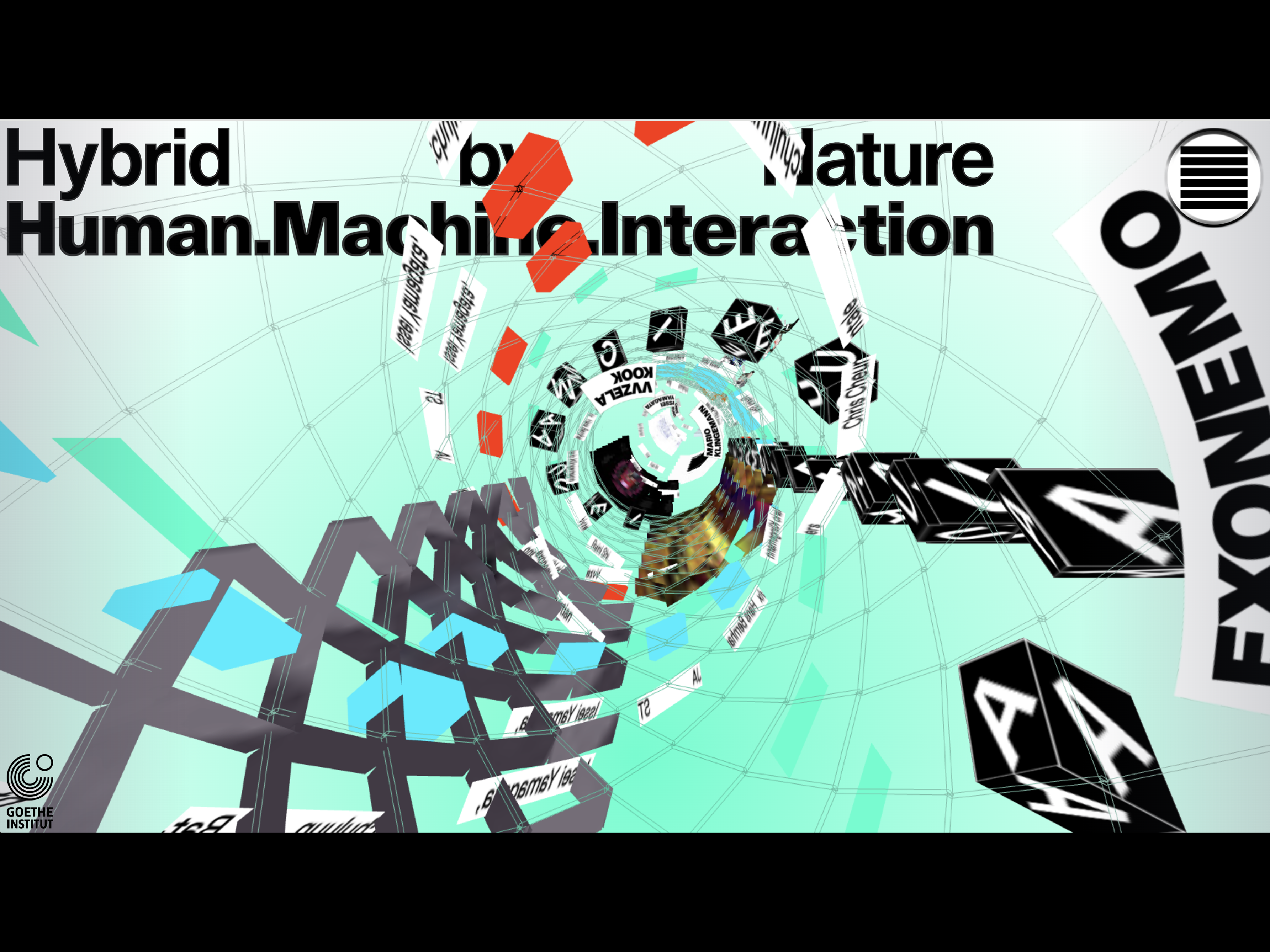

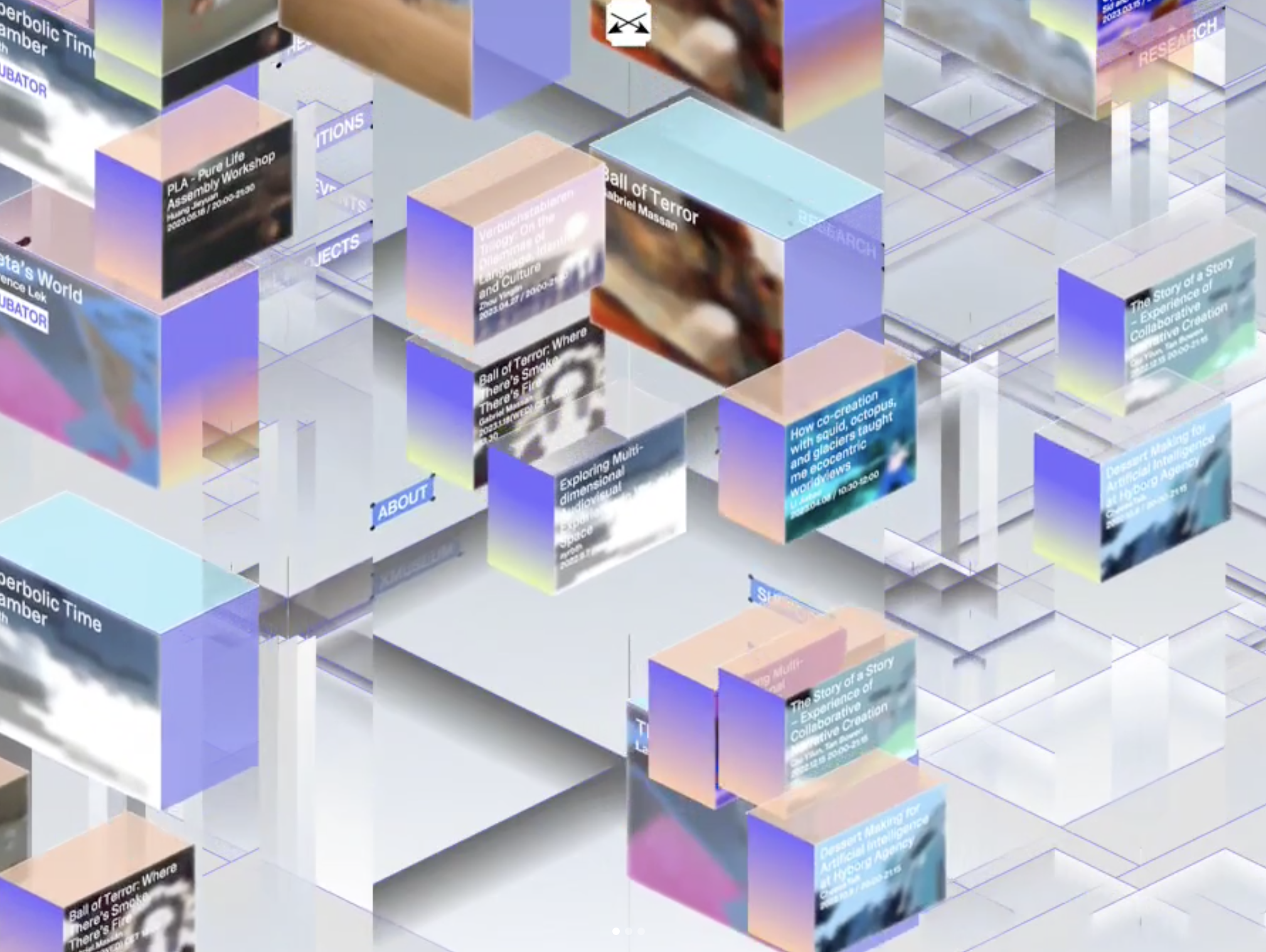

Structurally the digital world makes up for this lack of “human” quality by over-compensating and over-charging the limited sensorial access. Digital design often tries to be hyper-stimulative; complex algorithms, screens packed with information, and endless-rolling videos. I can see how this is a successful technique to confuse users and distract them from noticing the lack of material experiences. This is what we need to be aware of. It’s not necessarily damaging to replace some of the things that used to be physical with digital counterparts, but it can be deceiving if we lose the awareness that these are very different ways of communicating – and many things get lost in translation.

(MZ) It’s fascinating to see how your projects explore the interaction between physical and digital objects; completing each other in their functions these question our relationship between material and digital reality, and how it affects the inner and outer spheres of humanity.

(YS) I think this is where the term ‘dynamic circulation’ sits. My work refuses the idea of a total separation between digital and physical. I like to think of it as jazz music; instants of collaborative harmony can be created by the careful balance of the elements at play.

My inquiry is motivated by the awareness that we can feel and encounter the digital and physical spaces simultaneously but have very different experiences. With my work I question where and how these kinds of collaborations are possible. Not everything I make might be easy for the audience, but I like to present things that haven’t been explored yet. There is always the hope that this conversation will develop as more people critically engage with digital media.

(MZ) Data are ultimately something we create but do not completely comprehend, or somehow that never fully reacts how we’d expect. This resonates with how your work exists; sites and platforms seem to behave erratically, independently, and sometimes completely against our will.

(YS) I think coding and computation have an intrinsic beauty, they can create their aesthetics, rules, and patterns. This is where the ‘erratic’ feeling emerges in my work. When we think about the interaction between machines and humans, the fundamental element to question is the role of the user. This part of the research allowed me to shift my role towards the one of the “mediator”, who introduces these ‘erratic’ aesthetics to the users. This is also where my work challenges the public: to truly question your position as the one who interacts with a system is to shift your approach towards the media you’re using.

(MZ) User awareness can be a powerful tool; it makes us question why or how systems are designed to provide the service we are in need of. It also opens a conversation on digital ethnography – Are we all the same user? Have we all the same needs, the same logic and patterns? In an English-dominated universe, the web seems set on downgrading diversity in order to create predetermined pathways. Ultimately we are precluded the freedom of independent choice.

(YS) My research turned when I realised that the internet and the web are very uneven fields and that our capacity to play with them is in fact very limited. Growing up in a small country in East Asia and living in Western countries showed me that ownership, interaction, and experience can be very different according to linguistic barriers and cultural diversity. I absorbed this criticality as part of my practice; not only to add an international voice in a digital reality where English still represents more than 50% of the content, but also to bring awareness to the people in my country of this cultural disparity, and instigate them to become active users.

(MZ) When we think about the user in relation to digital platforms we are confronted with a standardised dictionary, a set of ill-defined targets that websites and apps have to meet to secure a prime spot in the crowded web space. User-friendly, responsible design, accessible content, and usability, are just a few of the terms we encounter daily. With your statement: “Seeking Uncomfort on Comfortable Websites”, you toy with this language whilst also making a clear definition of what’s central to your enquiry.

(YS) I’ve been interested in how terms such as ‘comfort’, ‘user-friendly’, ‘easy’, and ‘accessible’ are used in the realm of big technology. These words disguise themselves as universal and inclusive for all users. If you start unpacking their meaning and how they shape communication, these ‘comfortable terms’ often benefit the companies more than the users.

I see a huge criticality in the language we attach to digital design, mostly coming from a market-driven interest in levelling diversity, boxing users in pre-determined paths, and ultimately removing freedom of choice. Comfort feeds the human conditions of estrangement towards systems that we still don’t understand; they pretend to provide us with a more “human” experience, whilst actually, they rank us up to make our choices more predictable and speculate on it.

(MZ) There is perhaps a need for a new dictionary to be found in digital design; you seem to propose a new language on your website. Many fascinating terms instigate a different perspective on what we are about to experience: “dynamic circulation”, “narrative architecture”, “anti-friendly”…

(YS) I always think that the right circulation between offline and online is important. We can’t be only offline or online, the world – for those already heavily connected to the internet – is becoming an in-between space. Dynamic circulation comes from the question: how can we dynamically move between these two environments as proactive users, instead of blindly following given instructions?

The idea of narrative architecture is my proposition in response to the concept of dynamic circularity: a methodology that allows us to weave data coming from the physical environment and our immediate context in order to establish constructions of computational nature able to retain the tissues of our interaction with reality. The definitions or wordings are very flexible, though. These are vocalising my ongoing effort to understand what I’ve produced and what I need to do for a better future.

(MZ) Talking about language, your work is permeated with words and typography. These are never stable, they disregard the ties imposed by constraints like accessibility.

(YS) I loved what Tobias Frere-Jones said at the Typographics conference in 2016: “Typefaces are solutions to things, and we need more typefaces because we keep having problems.” I like to think that the way I can use typography in my work somehow responds to, or highlights, the criticalities you incur when working with language and signs in a coded reality.

(MZ) Opposite to the way letters, numbers and signs behave on the printed page your language is activated by a perpetual sense of flux. Words bend and twist, performing actions that are perhaps unnatural to the traditional way we understand linguistic signage.

(YS) I always think of my work as a test to find solutions or a quest to find collective answers. In the process of choosing and testing typography, I’m looking for the right voice that can bring me closer to finding solutions. I never set on what’s expected, and I always like to challenge the way we acquire information. Again is an active choice of gaining distance from the mainstream, the big tech language, the standardisation. I like how language can be expressive and performative, and how words can carry emotions we may miss on the web.

(MZ) Linguistic and visual games can help us tackle complex subjects and inexplicable things, especially in a digital reality where perhaps the primary stimulation is visual. It seems that research of this kind is taking you to explore unexpected realms.

(YS) At the moment I’m focussing on the coalesce of research process, finding the right audience, and narrative methods for complex topics. For example, I’m working on a series of coming exhibitions that will explore broad, complex areas of study; digital colonisation and digital justice are some of the themes I’ll be unpacking through my upcoming projects. New exciting research directions are opening as technology develops and society evolves alongside it.