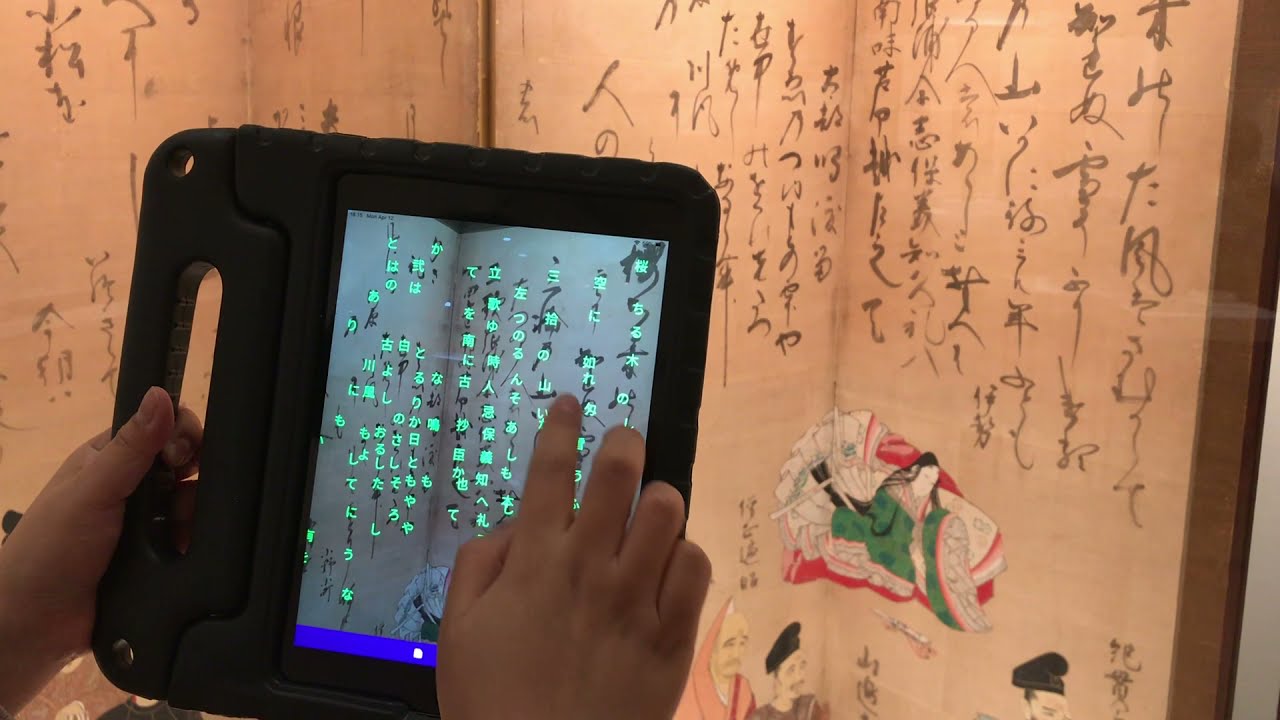

The prototype of the Miwo app, an AI-based character recognition system. Source: ROIS-DS Center for Open Data in the Humanities (CODH)

The Japanese writing system is well known for its complexity. To even write the most basic Japanese sentences, knowledge of three scripts is vital: Hiragana, Katakana (two sets of syllabic alphabets), and Kanji (thousands of Chinese characters). Each of these has specific roles in a sentence, so it is essential to master all three scripts to read and write in Japanese. This complex system serves as a barrier, making the land and its culture harder to access from outside.

But there is another, less well-known, barrier inside Japan. On account of several writing reforms that took place in the second half of the 19th century, most Japanese natives today – including me – are unable to read books produced just 150 years ago. This means that the country suffers from the difficulties of transmitting its own past knowledge to modern society. In Japanese libraries and households, there are millions of books and billions of documents that have been waiting to be read one day.

Kuzushiji or obstacles to reading pre-modern Japanese texts

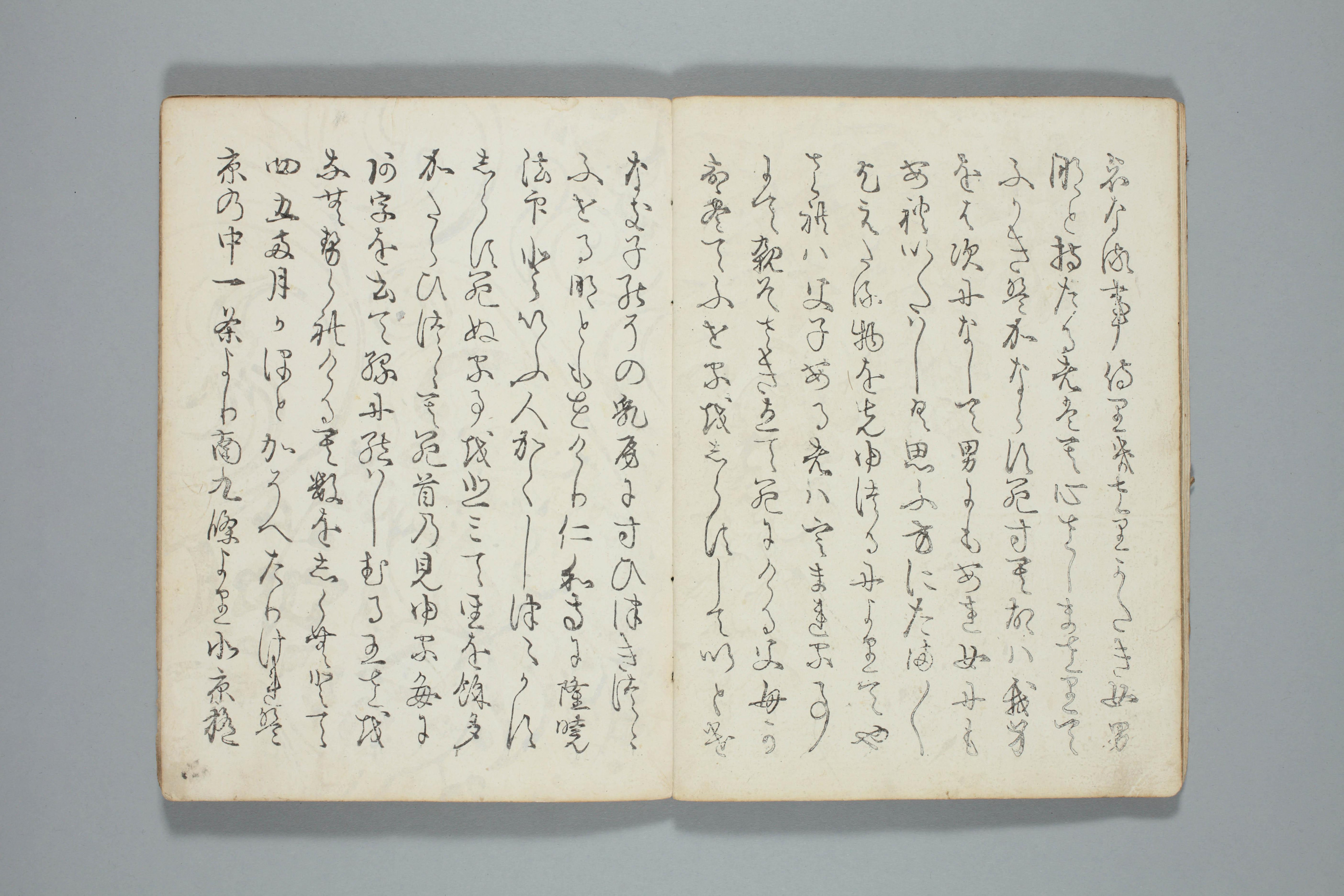

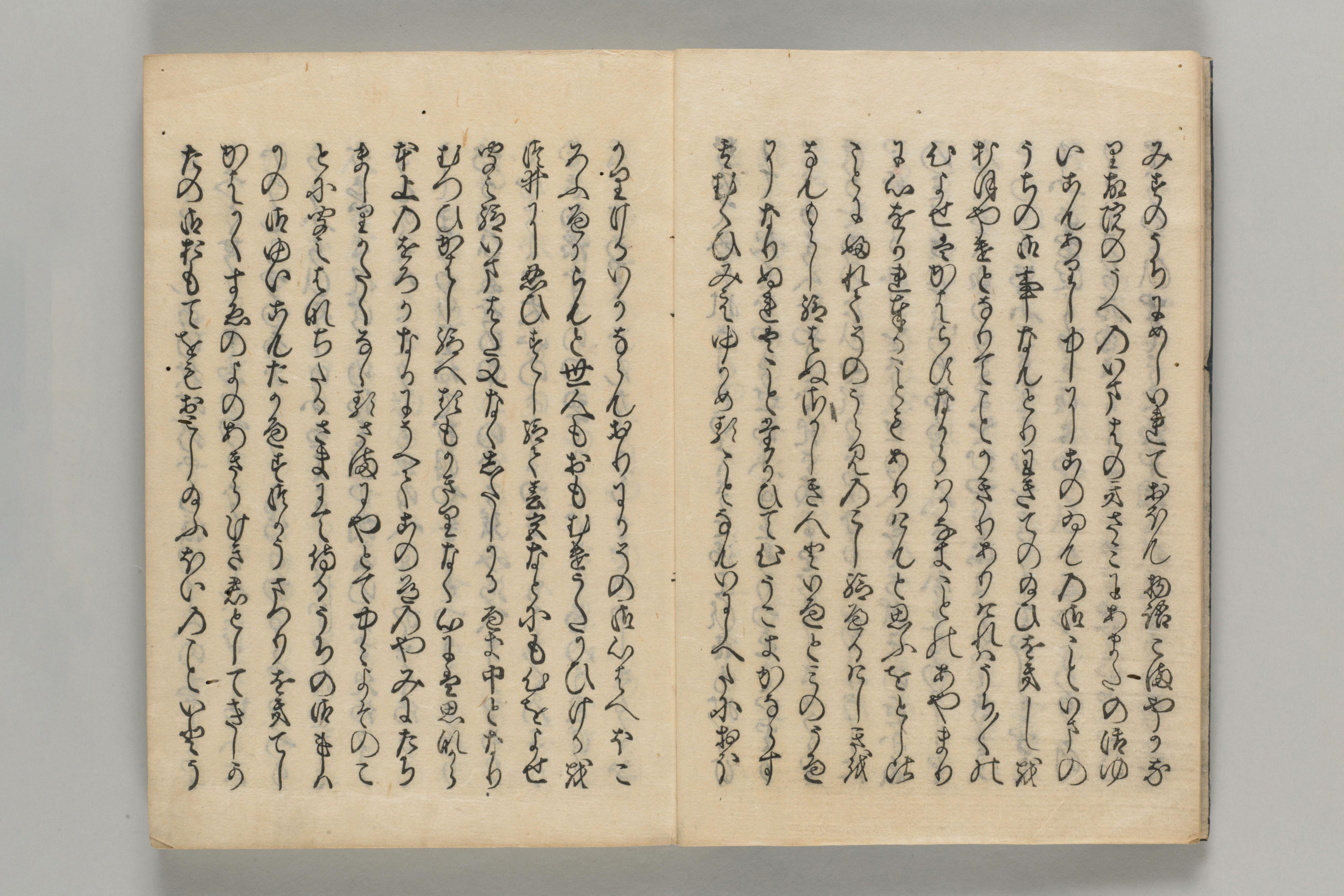

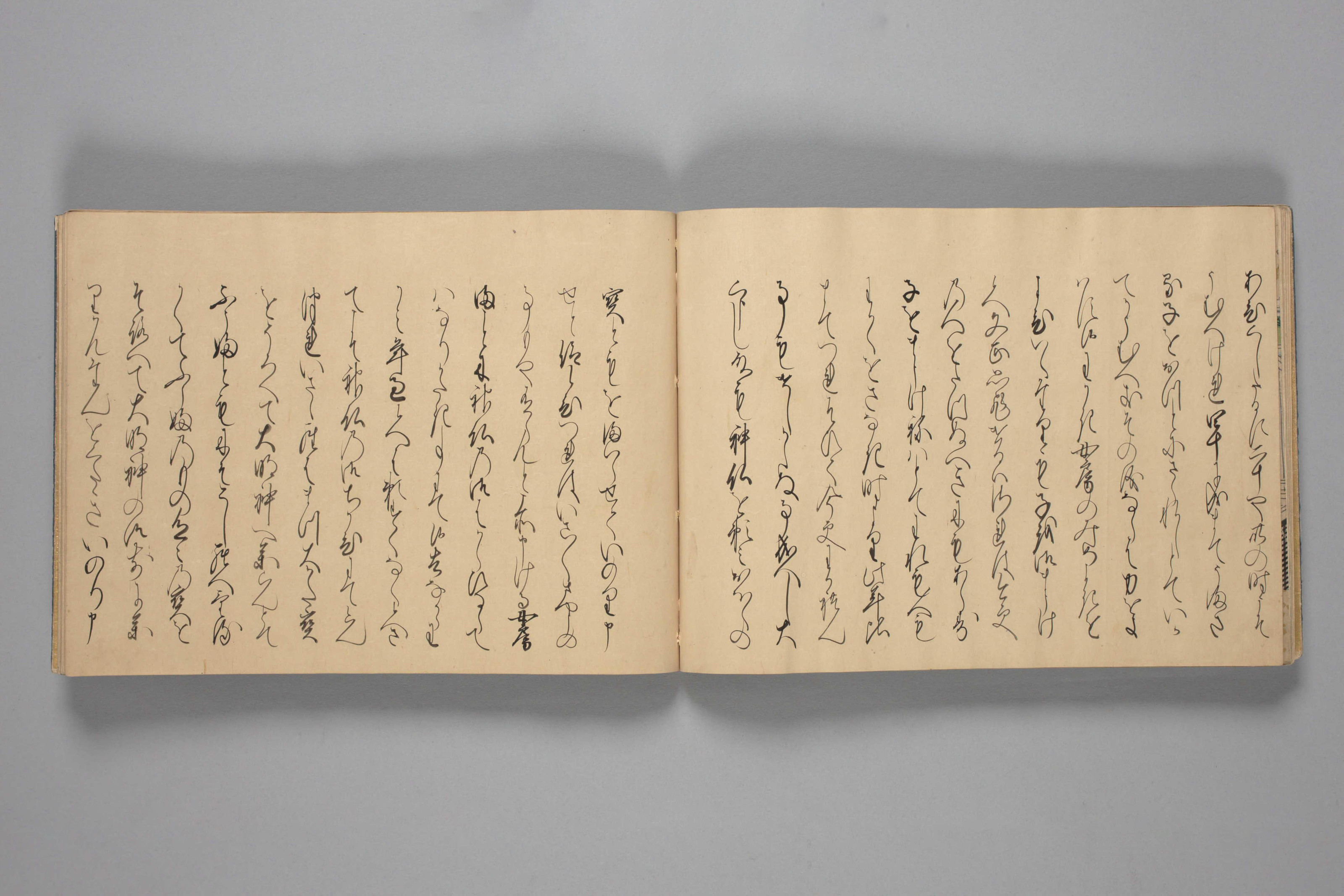

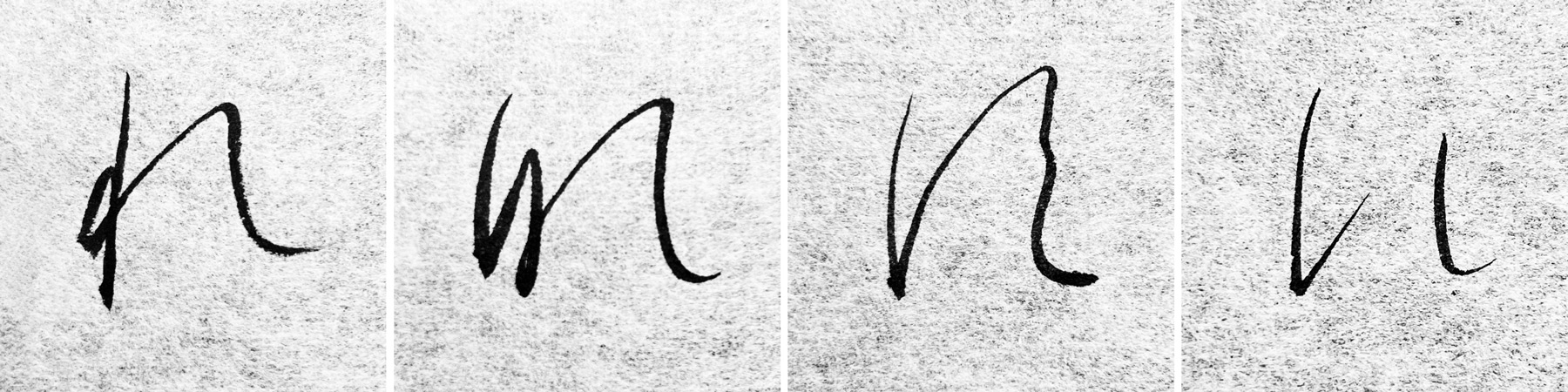

There are two major obstacles to reading pre-modern Japanese texts. The first obstacle is that pre-modern Japanese texts are printed (or written) in an extreme form of cursive. In this style, identifying the original characters is a challenge. Not only do they look different from today’s Hiragana, but they also wildly connect to the preceding and the following characters. It is even hard to recognize the beginnings and ends of each character.

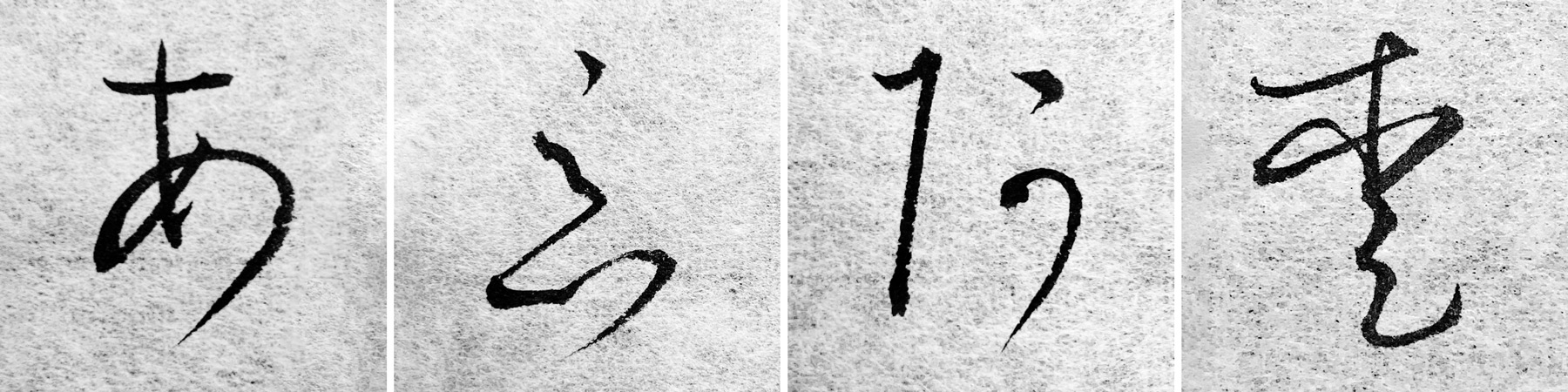

The second obstacle is that, unlike today’s system of strictly one-character-for-one sound, there used to be many ways of writing one sound in Hiragana. That means you need to remember at least three, sometimes more than ten variations of the Hiragana character. Some alternate Hiragana shapes look identical to Kanji characters, too. The only way to recognize them correctly is to determine them from the context.

These characters all represent the sound A (あ). The first one is the only recognizable character today.

These characters look very similar yet represent different sounds: from left to right Re (れ) Na (な) Su (す) E (え). Again only the first one matches today’s convention.

This rather particular form of writing is known as “Kuzushiji”. Kuzushiji had been in fact in use for over a thousand years, but nowadays only trained experts can read it.

This is why I was extremely impressed when I read about Dr. Tarin Clanuwat – a young scholar from Thailand – who developed an AI-based character recognition system, which magically transcribes pre-modern Japanese characters into contemporary Japanese characters.

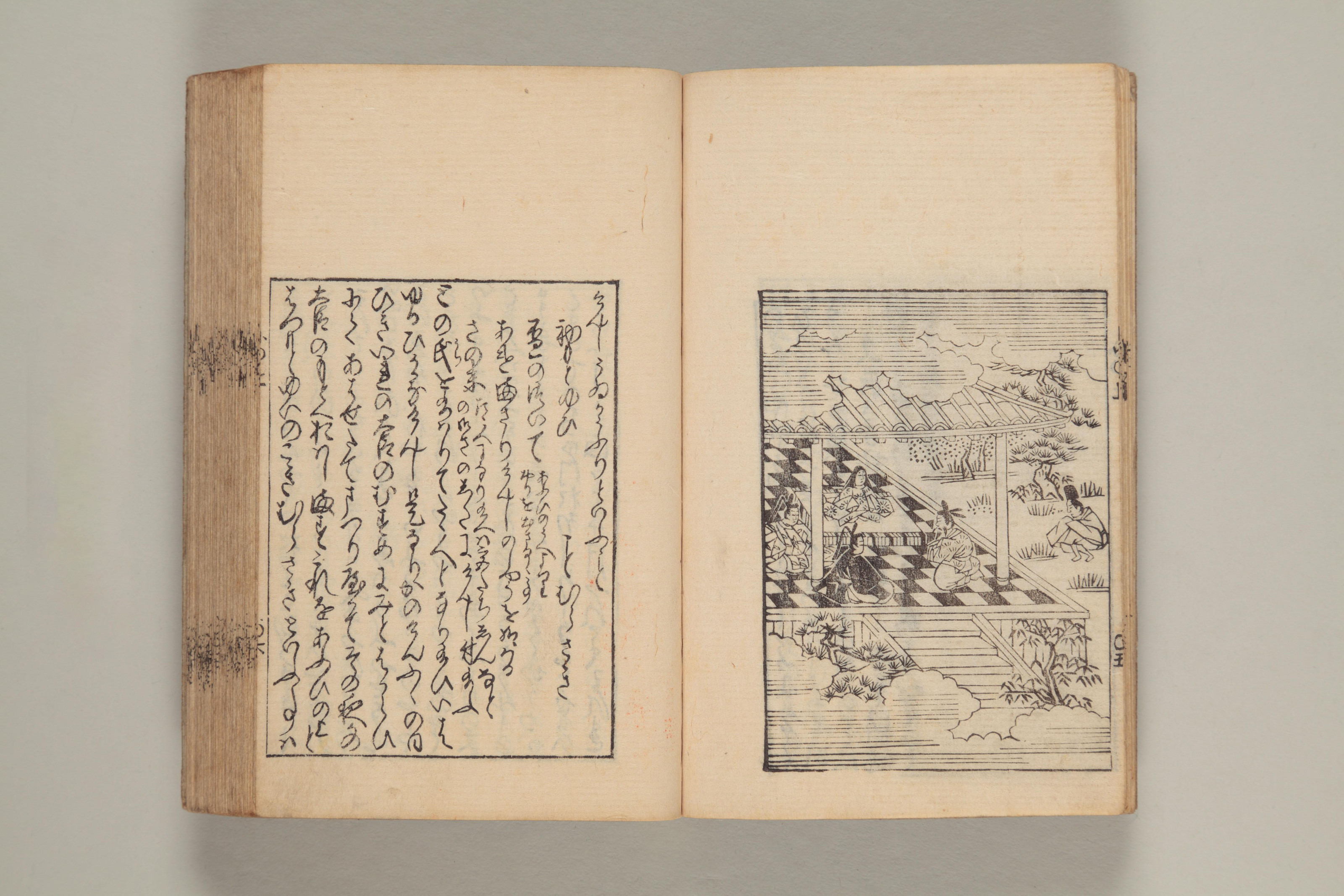

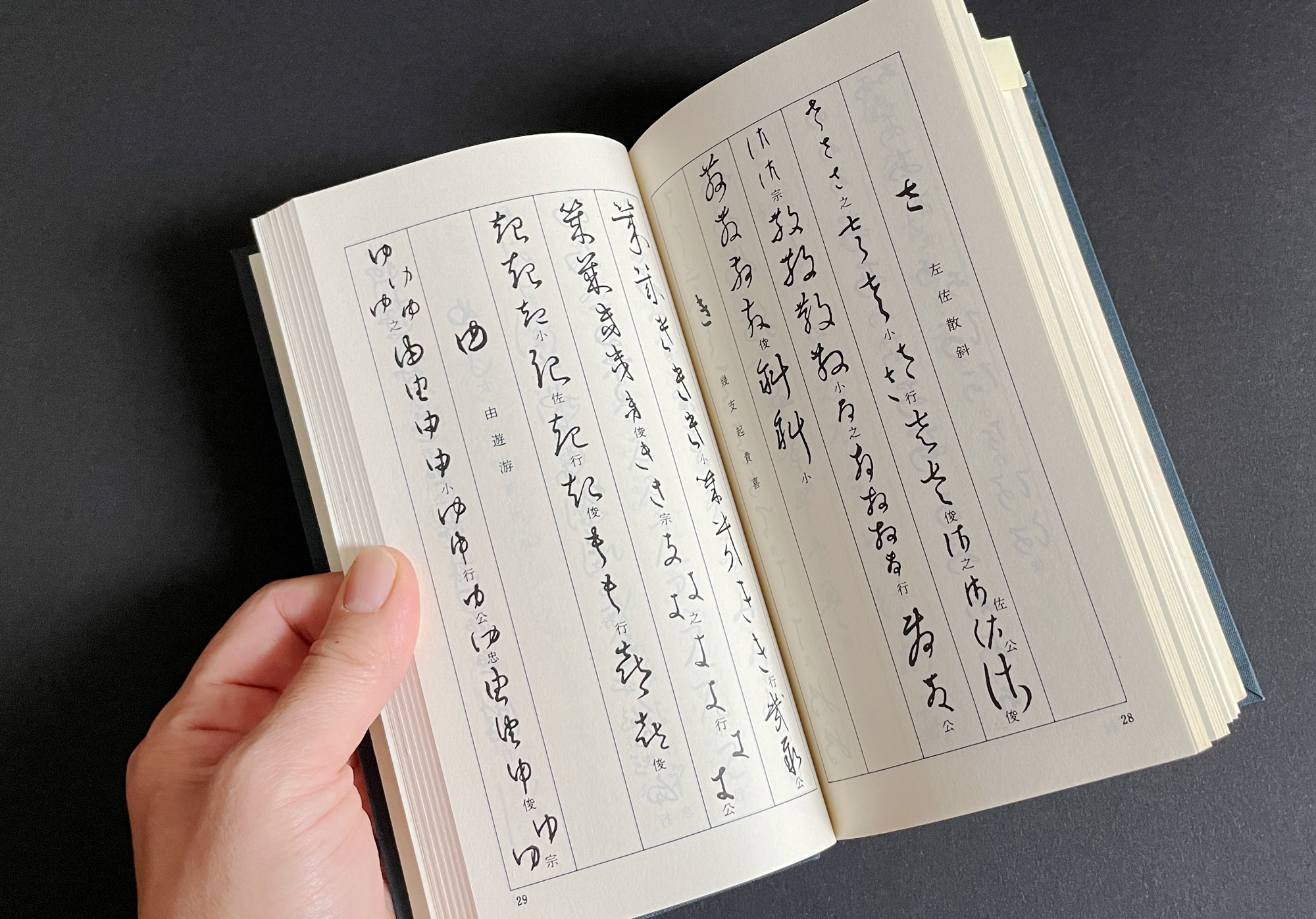

The conventional way to read or write Kuzushiji is to use a calligraphy dictionary such as this.

Fascination for medieval Japan

Tarin has been fascinated by Japanese culture since her childhood. As a teenager, she taught herself Japanese but her interest at this stage was still Japanese culture in general. As a university student in Thailand – she majored in Japanese, of course – she encountered her true passion: medieval Japanese culture. She was captivated by the manga version of “The Tale of Genji” – a masterpiece of Japanese literature written in the 11th century. In 2008, Tarin moved to Japan to take a postgraduate course in Japanese medieval literature. The major problem she encountered there, however, was: Kuzushiji!

Being able to decipher Kuzushiji is an essential skill in her subject, yet gaining proficiency in it is a challenging task. Having once failed an exam on Kuzushiji, she thought “Well, if I could write it myself, I should be able to read it!”. Tarin signed up for calligraphy lessons and eventually achieved not only her initial goal (of being able to read Kuzushiji) – but became an excellent calligrapher as well.

Tarin standing next to a calligraphic piece of hers, which won an award.

AI object-detection for Kuzushiji recognition

Even though she was armed with specialised training, reading Kuzushiji remained an extremely laborious task. Gradually, Tarin contemplated the idea of automating it.

Because of the idiosyncratic issues of Kuzushiji – the complexity of the Kuzushiji and the obscure layout of Japanese books – the conventional optical character recognition (OCR) was incapable of providing reliable results.

So Tarin had the idea of utilizing an object-detection algorithm, which is used in medical research to analyse images of cells. Unlike conventional OCR, which first configures the layout, then moves on to recognize individual characters, object detection enables the system to simultaneously identify multiple items and levels on a page. The organic and complex way of Kuzushiji writing apparently reminded her of cell images – and this unconventional approach turned out to be a great success. It provides significantly more accurate results than conventional OCR methods.

Using an object-detection algorithm had the advantage that it is a well-researched area, so there were many existing models to try out. Tarin and her team assessed the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches, in order to develop the most appropriate system for Kuzushiji recognition.

After months of researching, making prototypes and testing, in 2019, Tarin and her team at the Center for Open Data in the Humanities published the first version of KroNet, a web app for professionals (mainly used by scholars). As one would expect, the KroNet system gained extensive attention inside and outside of Japan.

But she didn’t stop there. It was her passion to make historical materials written in Kuzushiji accessible to the general public. In 2021, Tarin and her team went on to publish a mobile app called Miwo, which can be downloaded and used by anyone.

Of course, I downloaded Miwo and used it – it is very easy to use and really fun! Transcribing the text on the spot is really powerful, as you can find Kuzushiji on so many historical materials – maps, ads and artworks. Until recently, I could only see Kuzushiji as some sort of decoration, but not any more with Miwo! The app will certainly contribute so much to building a bridge between the past, present and future of Japanese culture.

Miwo app in action. Source: https://tkasasagi.github.io

Lastly but importantly: the dataset – a great number of printed and handwritten characters – that was used to train the AI systems of KroNet and Miwo, is publicly available. It can be rich resource for type designers or design researchers to see historical forms of Japanese characters.

References

Papers

Clanuwat, T., Lamb, A., and Kitamoto, K. (2020). “KuroNet: Regularized Residual U‐Nets for End‐to‐End Kuzushiji Character Recognition”

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s42979-020-00186-z.pdf

Clanuwat, T. (2020)『くずし字認識の進化とサービス化の展開』

https://ipsj.ixsq.nii.ac.jp/ej/index.php?active_action=repository_view_main_item_detail&page_id=13&block_id=8&item_id=208670&item_no=1

Clanuwat, T., Lamb, A., and Kitamoto, K. (2019). “KuroNet: Pre-Modern Japanese Kuzushiji Character Recognition with Deep Learning”

https://arxiv.org/pdf/1910.09433.pdf

Clanuwat, T., Lamb, A., and Kitamoto, K. (2019) “A Human-Inspired Recognition System for Pre-Modern Japanese Historical Documents”

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8744232

Articles

源氏物語が好きすぎてAIくずし字認識に挑戦でグーグル入社 タイ出身女性が語る「前人未到の人生」

https://ledge.ai/tkasasagi-interview/

情報学から読み解く日本古典文学:はじまりは『源氏物語』

https://www.nihu.jp/ja/publication/nihu_magazine/037

Videos

Reading Edo: Data-driven Approaches for Japan Studies

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5qXY_bc12ag

The 95th International ARC Seminar

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6ww5gOFZqww

Tarn Clanuwat, MIWO: Kuzushiji recognition smartphone application with AI

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Qwnke7mLROQ

CDDP Video Series: Kuronet Kuzushiji Recognition--IIIF Curation Viewer

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J_joHge32JY

Tarin’s social media

Website: https://tkasasagi.github.io

Twitter: https://twitter.com/tkasasagi